Music as the most accessible expression of immaterial culture is naturally geographically fluid. All kinds of different music can be found in all kinds of different places. Nonetheless there are concentrations of certain kinds of music in different parts of the periphery that may be attributable to concrete or general processes having to do with the edge of the city. In general music is heard all over the periphery and usually it is a sign that people are working.

Urban Rock – Tlalnepantla

One of the constants of the megalopolis music scene is that the north of the city likes rock. Why this is the case is a question of conjecture. The north of the city lies on the trucking routes from the United States, perhaps this has some cultural influence. The north of the city has always been more industrial. And naturally industry tends to be built just outside of the city. Perhaps there is something to working in factories with their strict time schedules, repetitive actions and limited social interaction lending itself to rock music. Maybe somewhere urban rock is influenced by the sound of revving truck engines and pounding machinery. Or maybe it is the rock narrative of the working class hero which makes the north of the city fertile ground for urban rocks arrival in municipalities like Tlalnepantla de Baz and Ecatepec in late 70 and 80s.

So it is probably not surprising that the local heroes of Tlalnepantla de Baz are a rock group called Bostik after a brand of adhesive. Apparently all the band members were working in a factory producing this tape when they founded the band. Bostik is well known for crying the grito “Viva México” at the municipal palace during the Independence Day’s celebration in Tlalnepantla the 16th of December. The music is reminiscent of bands like English rockers Status Quo. The songs are about rebellion and the passing miseries of urban life. Young people can be seen sniffing glue at these concerts, holding their hand up to their nose as if sucking their thumb and smell of marijuana and cheap chemicals floats through the air.

There is an odd tension between the foreign origin of rock and roll to Mexican culture and the notion of rebellion against Mexican politics and middleclass values. Why should the sound of urban rebellion be expressed in the foreign musical idiom of rock, and frozen somehow in 1985? On the one hand the nationalist nature of the Partido de la Revolución Institucionalizada makes the foreign origin of the music of rebellion understandable. The extent to which the music stands still is harder to grasp. Perhaps it was never really about the music anyway, just the rebellion it expressed. Any deviation from its strict formal pattern would be appeasement and conciliation.

The concerts themselves generally revolve around a large number of bands, usually in more or less the same lineup, such Tex Tex, Lira ‘N Rol, Charlie Montana, Sur 16, Leprosy and others playing in convention centers, small stadiums and outside venues in the periphery of the city to large groups of young people dressed in denim and black t-shirts with the logos of bands on them. There is a clear anti-aesthetic present in the grimy lettering and albeit commercially bought Do-It-Yourself feel to the design culture. As if the whole look were based on the rejection and abandonment of social mobility. These concerts are a constant of the periphery and everywhere you will go you see the posters with the names of all the same bands on them, as if they were some kind of travelling circus of rebellion circling the megalopolis.

Musica Banda – Rodeo Texcoco

Ranchero is the music of countryside. It hence has a double appeal, first to the migrant to the city who is reminded of home, secondly and perhaps more importantly to the rural community being swallowed by the megalopolis. In this last case the music is a reinforcement of pride in rural identity when faced with the onslaught of urban and often global culture. Despite having a more traditional aura banda music is actually quite dynamic with new styles, artists and dances popping up all the time.

Ranchero music is meant to be danced to in couples with defined dance steps and rhythms. Since it is dance music for couples the themes are generally romantic. And since the bands are large and dancing in couples is more interesting in large groups of people reminiscent of village fiestas, the places where the bands play have to be big and orchestral with up to twenty pieces. In the case of the Rodeo Texcoco, a large, boxy, place with wooden tables and balconies overlooking a dance-floor and stage, the name says it all.

Values are conservative in the countryside. This is reflected in dress and behavior. Romantic dancing also invites to better dressing and more ostentation. Stylish boots, shirts and hats are worn. The musicians wear suits. And in a countryside destroyed by poverty success in itself is epic. When the music is not romantic it is about the migrant who crosses the frontier or the drugs lord who controls it.

As one would expect from music from the countryside it is very national in its scope though primarily being played by bands hailing from the north of the country. The bands playing in places like the Rodeo Texcoco are always part of a national or in the case of the famous Tigres del Norte in a North American circuit. They are rarely local bands from Mexico City, except in the case of the Angeles Azules from Iztapalapa.

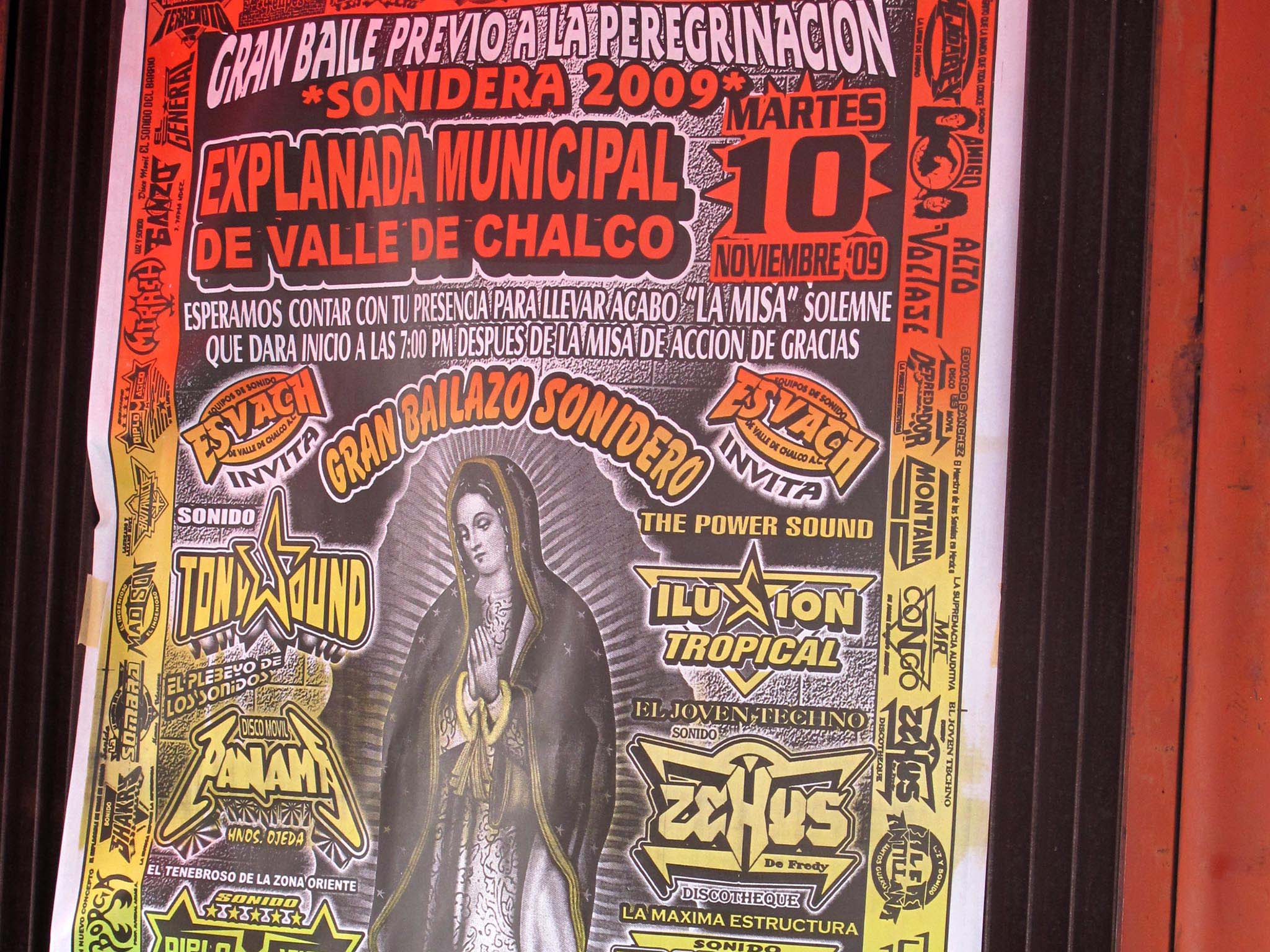

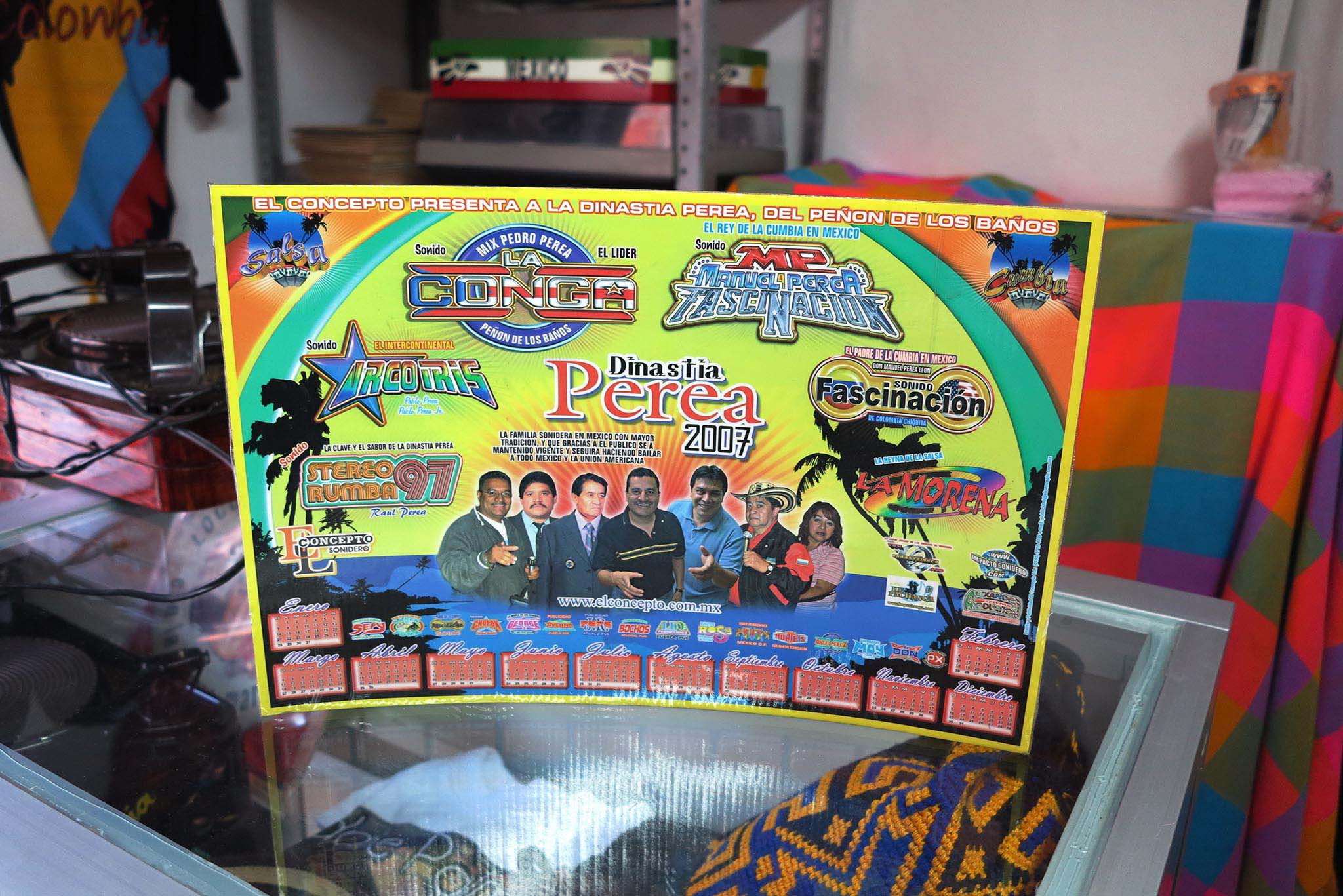

Sonideros – Peñon de los Baños

Another style of musical event common in the periphery are the so-called sonideros, the sound system deejays. These will often play at neighborhood parties, municipal fiestas or events such as the anniversary celebration of a market. They play tropical dance music and spectacular light shows have pride of place. Well-known deejays are Sonido La Changa, Sonido Condor, Sonido Sonorama.

This tropical dance music culture is rooted in the neighborhoods of Peñon de los Baños on the edge of the city by the airport known as the little Colombia in sonidero circles, and the central neighborhood of Tepito. These areas are both notable for their reputation as go-to neighborhoods for contraband during the 60s and 70s when Mexico was still basically a closed economy and goods such as imported records were hard to come by.

True to its origins sound system music is both international, highly Latin in its focus and working class. A retro-futurist aesthetic pervades the this culture as one would expect in a context of lightshows, high-voltage audio and technological prowess, the electric portal to the wider world of Latin American culture. Though the Latin American dancing styles such as cumbia and vallenato may themselves be rural in their country of origin, they are very urban in Mexico. International trends arrive first in the city, especially in the capital.

The dances themselves have a neighborhood block-party feel to them, generally functioning as an expression of barrio identity. They are often free, since they are hosted by one or another neighbor or neighborhood organization. The deejays themselves intervene a great deal in the music as mc’s. In a way these shows can be seen as a cheap way to replace the bands which usually would accompany the dance. Because they are working class they are active in many working class neighborhoods on the periphery.

Cholo Rap

Cholo culture arrived to Mexico from the United States through deportation. It is quite common to find Mexican Americans deported to parts of the periphery of Mexico City lost, bored and somewhat frustrated in an ancestral culture from which they are now alienated. Because the profile of migrants to US, poor, from rural families, seeking better opportunities is similar to migrants from rural areas in Mexico to Mexico City it is not surprising that returning deportees end up on the periphery in Mexico City more than in the center.

These returnees bringing with them US gang culture which in itself is an attraction for urban youth. Rap as a music form also has certain advantages. First of all it easy to perform in small social settings. You put on a cd with preferred beats and starts rapping over it. As such it blends into a party. A rap is also something you can work on while sitting in the subway or walking down the street. Rap doesn’t require expensive equipment. Rap lends itself to a gang setting if only for the simple reason you don’t need to carry (expensive) instruments around and accompaniment can come from a stereo system. On the other hand it is not easy and requires a lot of talent to do well.

A central theme of cholo or cholo inspired rap is the neighborhood, the barrio, which is central to the identity of street gangs. A street gang, or klika for the cholos, in the end is a territorial unit. Names making such references are for example the klika Valle Psycho for Valle de Chalco or the klika Ecateloko for Ecatepec. The most recurrent theme of rap in the periphery is the assertion of pride and prowess accompanied by a sense of territoriality – a message from a gang member to any potential invaders.

Perhaps for this same reason one rarely sees publicity for rap events or rap concerts. Like any subculture it flourishes among a small group of people, who in this case are bound by strict cultural and territorial ties while the city at large remains oblivious.

Indigenous Bands

A kind of musical event typical of the periphery of the city though not exclusive to it are the festivals of indigenous communities, usually to celebrate the saint of their village of origin. During these festivals the music of the village of origin is played. One type of community common on the edge of the city are indigenous migrants, often all from the same village and linguistic group who congregate together in one neighborhood on the edge of the city.

When one walks through these neighborhoods they look exactly like any other neighborhood, there is nothing specifically indigenous about them, yet in the end practically all the inhabitants may be from one very specific place and cultural group in another part of Mexico.

What makes a culture is the combination of elements. Just like hip hoppers need rap music, graffiti, breakdancing and deejays to express one cultural identity these indigenous festivities require dance, food, music and religious ceremony. And so the often poor communities need to buy the instruments for the musical accompaniment of their festivities.