On the edge of Valle de Chalco stands the vast hulk of the ex-Hacienda of Xico. One building is falling apart, a jagged tear cutting through it like lightning. The building is built up against the side of the Xico volcano. From a distance it seems a low wide hill set among the grid of self-built housing that is Valle de Chalco, though on top you find yourself in front of a wide shallow crater full of corn fields. According to the locals this is the xico in Mexico, the navel of the moon, a name that doesn’t seem so strange as one looks out on the dreamlike landscape of the Valley of Mexico. The volcano was once an island in the lake with its greater cousins the snow-topped Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl towering behind. I was told later that the lake was partially drained in the late 19th century by the owners of the Hacienda to expand their lands.

A graveyard stands on the shoulder of one side of the volcano. It being just after Day of the Dead it was full of wilting orange flowers. A young woman stood drinking beer from a can next to grave while a musician stood next to her playing guitar and singing. This cemetery was a good place for buying the pre-Hispanic statuettes and pottery found by the gravediggers as they scratched among the earth a worker in a nearby shop told me.

On another flank of the volcano stood a large half-built social housing unit of the developer Ara. I was told later by people who had worked on its construction that idols had been found and destroyed in the building process. One way or another it seemed odd to have such an ordinary, cheap social housing unit built on such a unique site. Beyond that building had stopped because of problems with the municipality. The gods of Xico were avenging themselves.

Part of the ex-Hacienda was now a cultural center with a small museum. The site was spattered with half-kept gardens, ruined walls and pepper trees. I entered the ex-Hacienda and saw a group of teenagers in the colonnades around the courtyard. They were studying theater. One large boned, bubbly girl had aspirations to become an actress.

I walked to one of the classrooms where a slim, middle-aged man with a small, sharp-featured, lively face was teaching two children how to draw. One of them was a young adolescent, chubby and dark in his jeans and baseball cap, who stared sullenly in front of himself. Another was a quiet girl of about eight with black hair.

A great deal of drawing does take place in Valle de Chalco. Commercial signs are hand-painted. Adolescents’ graffiti over them. Tattoo artists are common and some even travel around the country to work in different regions of the country.

He told me that there was little interest from people in Valle de Chalco in cultural activities. Yet he was pleased with his few students. He particularly praised the young girl with black curls sitting next to him.

The teenager sitting sullenly across the table with his arms crossed had been put in the drawing class by his parents. He had been caught too often painting graffiti. The teacher, a muralist and graphic artist, Alberto Diosdado, allowed that sometimes graffiti had artistic value but that most of it was trivial and ugly, a crass expression of “Here I am.” To be a painter is to have a responsibility. He had painted a mural on the kiosk of Valle de Chalco. And he could charge money for what he painted.

The adolescent looked up from the table.

“If I had been given money for every wall I’ve painted on I would be a millionaire by now,” he said sarcastically.

Diosdado said you can get paid to paint, but you have to do it well.

He asked if I would allow him to do a portrait of me. I said yes and he took a sheet of letter paper and a ballpoint pen. The pen flew over the page without pause as he asked me to talk about my trip. A few minutes later he passed me the sheet with my likeness. Like in a mirror I stared off the page with wide eyes – a long, continuous swirl of blue lines.

He said I should get it framed. I rolled it up and put it into my bag.

I left the former Hacienda and walked to the central square of Valle de Chalco – a large, bare, modern rectangle of cement with a functionalist mayoral building along one side. In the middle stood a kiosk.

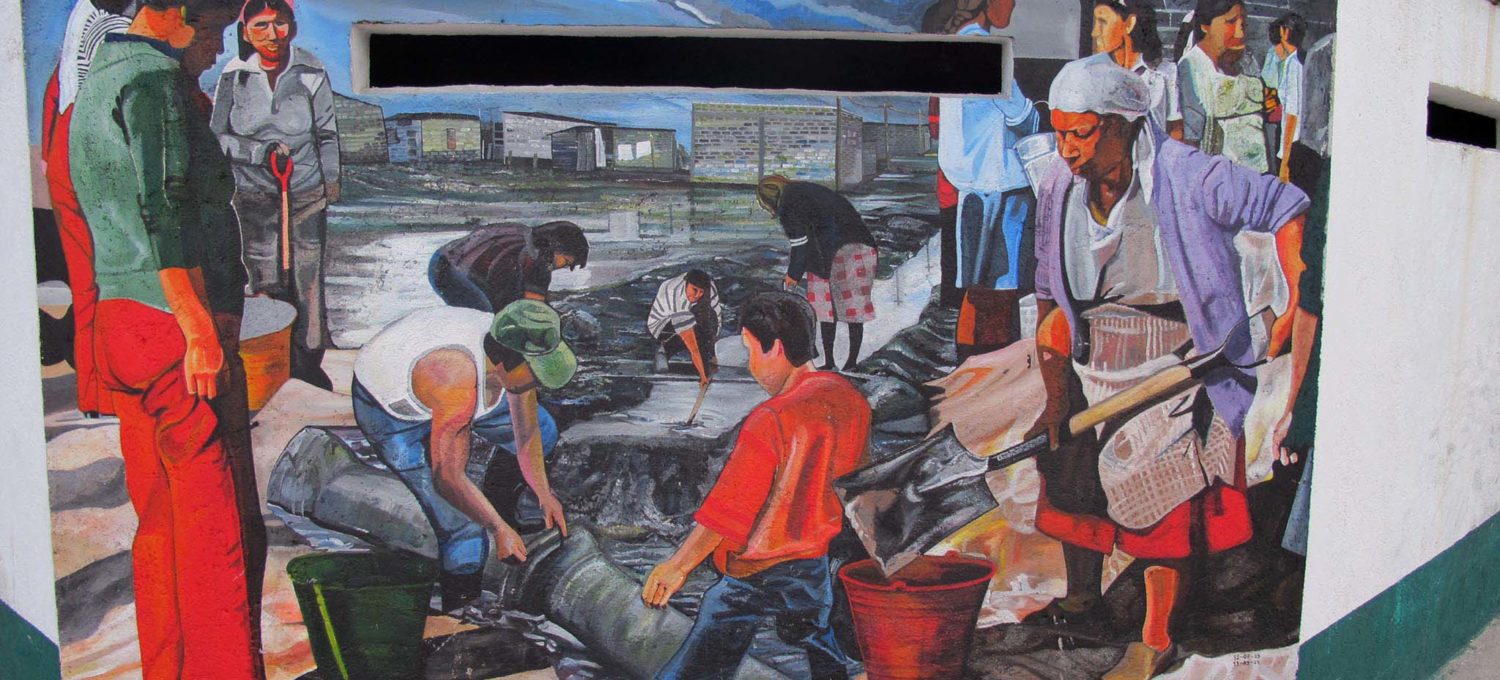

On one side there was a mural about the size of a garage door. It showed the building of Valle de Chalco by its people in the swampy lakebed in 80s. Women with wheelbarrows stand around men digging a pit for the drainage. Shacks lie amid the swamps behind them. Yet all maintain an air of dignity and determination. The mural of the genesis of Valle de Xico somehow reminded me of paintings of the founding of Tenochtitlan, the Mexica capital, on an island in the Lake of Texcoco. I left the square heading out of the municipality.

A small fringe of older buildings at the foot of the volcano showed where the village by the Hacienda was. The rest of the plain down to the shimmering surface of Lake Chalco was uninterrupted, grey, cinderblock, self-built housing. The volcano rose sheer to my left.

As night fell I headed over the flatlands of Chalco to the east looking for a place to stay.