That morning I continued up along a country highway toward the musicians of Santa Catarina, aware that the next day would be the name day of Santa Cecilia patron saint of music. I did not want to miss this occasion after having strayed off my route to get there. The east of the city is bordered by three large volcanoes though two, the Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl, get all the recognition. The third hovering over Texcoco is called Tláloc, smaller and less spectacular than its mythical brethren, appearing more like a broad rounded mountain. It is however one big volcano with slopes covered in oak and pine, green pastures and fields of corn. Creeks ran down through rocky ravines and a comb of hills ran up before its knees. These hills the great tlatuani of Texcoco, Nezahualcóyotl, had chosen as the site of his palace with its aviaries, aqueducts and libraries.

Clouds hovered above the crown of the volcano where I knew there was a pre-Hispanic observatory. Santa Catarina was one of three villages speaking the Nahuatl language of Nezahualcóyotl lying under the volcanoes peak. Pre-Hispanic astronomers used the mountaintops of the basin of Anáhuac as astronomical measuring points. Pyramids were built so that on important days such as the winter solstice the sun would come up exactly over the peak of a volcano on that day. And one can still see the sun rise on the 21st of December from the important ceremonial center el Cerro del Judío in the Magdalena Contreras. The great Templo Mayor on the central square of Tenochtitlan was built to align with the mountains. When the city was conquered the ruins of the temples still determined the direction of the streets in the historical center. And so the Aztec calendar is still engraved on the city’s grid.

I walked up the snaking highway among the trees and water running off the mountainside. Reaching the plateau on which the three Nahuatl villages of the Tláloc were situated.

I turned right, off the road down into a valley. A sign at the bottom said swimming pool: twenty pesos. There was no gate and the dirt road continued over the grounds of this small bathing place up in the mountain. I continued on. A middle-aged woman and her young son were raking leaves in the lawn next to the pool. She asked whether I was going to pay the entrance. I replied that I was not going to the pool and didn´t see why I should pay twenty pesos just to cross to the other side of the lawn. She told me to walk back. I told her I just needed to get to the other side of the lawn, I wasn´t going back up to the road. She said hurry along then, before we give you a beating. She said, if they fought each other between villages, what did I think would happen to me, an outsider, if the commanders of the mountain encountered me wandering through the fields?

I turned and said goodbye going forward along my path over the mountainside to Santa Catarina. I quickly regained the highway and walked into the village. Occasional sounds of music instruments being practiced came from some of the houses in the fields around the small village.

There was little activity in the village and stalls were either closed or closing. Night fell and it was dark. I inquired whether there was a hotel in the village. There was not.

I went to a small police office in the city hall and asked where I could sleep. They said there was a hotel with cabins about 10 kilometers down the mountain. I could get a bus. I explained to them that this was impossible because I had to walk the whole trip. I couldn’t take a bus. I needed a place to stay in the village. The round small, tough young policewoman in charge discussed it with two other officers. They said there was a building toward the edge of the village that might be suitable. But there was a man living on the outskirts who would probably assault me and they abandoned that option. Finally they decided they would ask the delegate and made a call.

A man in his fifties, thin and sturdy, chain-smoking, with a blue wool coat and short hair walked into the police office. He told them the situation seemed under control, though there was a threat of violence due to some feud playing out during the festival days. Then the chubby young sergeant explained to him my particular dilemma. Apparently I had made some vow and had to stay in the village.

I explained the project to him and told him it would be impossible for me to walk down to the hotel and walk up to the village again to hear the musicians playing Las Mañanitas for Santa Cecilia’s birthday in front of the church at sunrise.

I asked him about the village. Everybody here was either a musician or floral arranger. The village provided the floral arrangements for the residency of the president of Mexico, Felipe Calderón. He himself had worked at the airport but had come back to the village when he had retired, and they had elected him delegado or mayor according to local custom. We went to eat one of the houses where there was some kind of party where people were seated in rows eating pork and greens.

Finally he remembered a shack owned by his wife with a bed. I said goodbye to the police officers and accompanied him to the shack in a small vacant lot just off the village center. He turned on the light and I saw the bare shack with its wooden walls, metal frame bed and pressed dirt floor. Gratefully I walked in. The delegado departed. I took off my shoes and went to sleep in the bed next to an altar for the dead with bananas and beer next to an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

It was still dark when I was woken by the crowing of the roosters. Hurriedly I put on my shoes and clothes. I rushed through the morning dark, threading through the houses to the church.

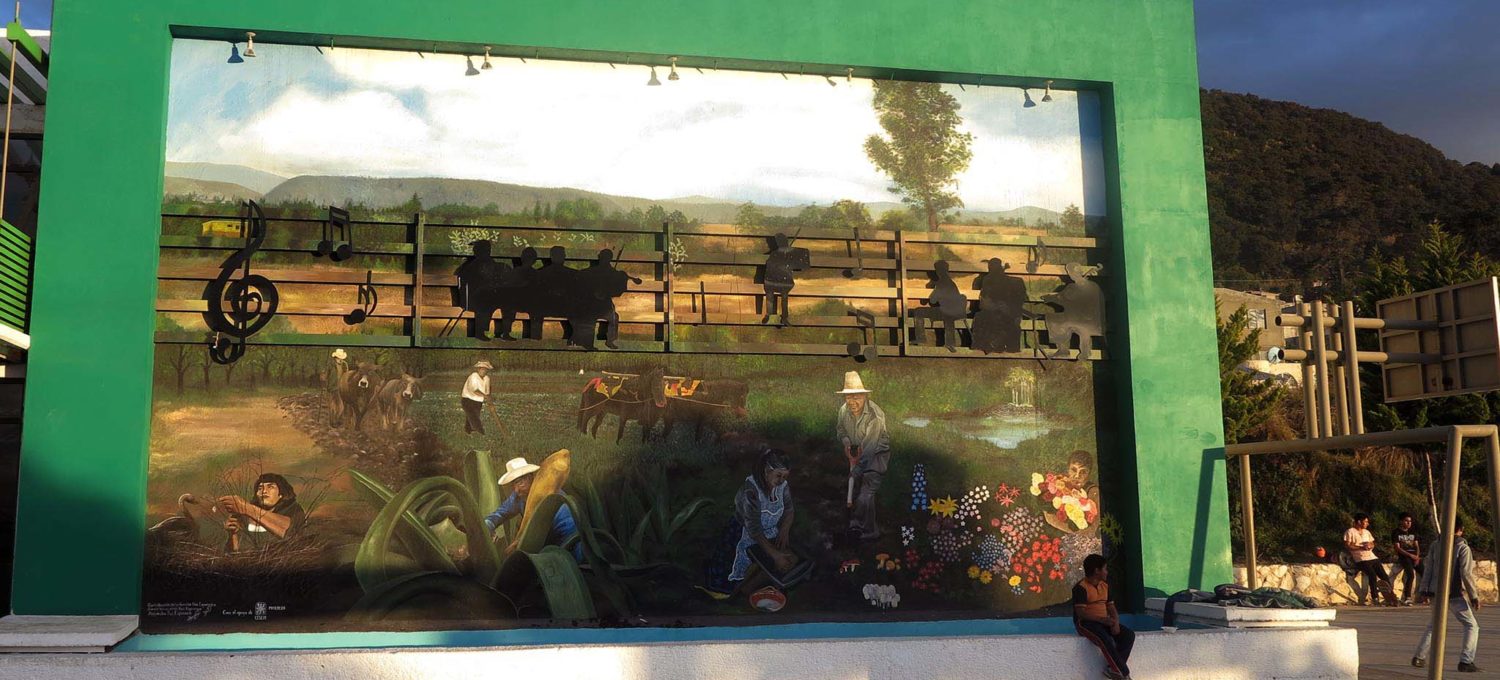

When I arrived there the courtyard was dark and empty. Then a young man came with thick down coat, vapor coming off his breath in the cold morning air and with a trumpet in a bag. He told me I was early and that the rest of the musicians would be coming soon. And so they did, entering the courtyard, one by one or in groups carrying trombones, tubas, double bass, violins, flutes, clarinets, saxophones and drums. Sometimes I would see three generations together, an old man, a young man and a child. The musicians formed in sections, woodwinds, brass, strings and percussion. They came together without any kind of guidance as if they had been doing this all their lives, greeting each other in the cold, recounting the year’s adventures as they rubbed their hands together to keep warm. After a quorum of about 25 musicians had been reached, the doors of the church opened revealing a statue of Santa Cecilia playing her harp. As the sun rose they began to play a lilting symphonic version of Las Mañanitas, Mexico’s birthday song.

More and more musicians kept coming, entering into the tumbling melody without missing a beat. The sun rose over the musicians playing on the little church square.

They stopped after about an hour and I was invited for breakfast by the leader of one of the many marching bands that Santa Catarina had produced.

Flowers and song was the Mexica metaphor for the purpose of life – fleeting and beautiful. Though this village lived off these and spoke Nahuatl I was told that both traditions were young, having grown over the past three decades. The village was now producing directors and sending people to conservatories. They played Strauss and formed their own 100-piece philharmonic orchestra when all the village’s musicians were in town. Somehow they had come full circle.

I left the musicians and breakfast and descended the volcano, the swirling tones of scales and chords, riffs and arpeggios rolling down the slopes. The city spread out beneath me. It was time to go back.